ABOUT THE DICTIONARY OF FABRICS: CULTURAL MEMORY MATERIALIZED

“I will deeply put the fashion on / And wear it in my heart”

—Henry IV Part 2

The Dictionary of Fabrics is a project that aims to help students of all disciplines and walks of life engage with fabrics and fashion terms mentioned in Early Modern English literature, especially as they appear in Shakespeare’s works. Shakespeare is rarely taught from a queer perspective. Students should know that while Shakespeare was married to a woman, he wrote 126 sonnets that were addressed to a young man. Horrified, his editors changed the pronouns from “he/him” to “she/her” to eradicate any hint of homosexuality. Not only was this unfair and deceptive—it denies LGBTQ students the chance to recognize themselves in his poetry. It also distorts Shakespeare’s identity and paints him exclusively as a straight white guy who some argue should be eradicated from the canon. His works create a framework for discussing issues like human rights, sex work, women’s empowerment, women’s labor in the manufacture of garments, laws surrounding clothing and class at the time—and fabric’s role in the subversion of them. We need to continue to teach his work and to ensure that the ways we teach it are not dismissing queerness in these canonical works of literature.

This resource is designed as a companion to Twelfth Night (1601), Measure for Measure (1604), and The Winter’s Tale (1611). I love teaching Twelfth Night because the play focuses on sexual identity and gender, two topics that remain incredibly relevant today. Measure for Measure presents an excellent take on gender roles and gender as a performance. The puns and jokes in The Winter’s Tale, especially those related to fabrics, comment on women’s sexuality and class status. For example, when Leyontes erroneously beliefs his wife to be adulterous in A Winters Tale, he calls his wife a “flax-wench.” In our current context, it might be hard to understand how the world flax could be employed as an insult, but during that time period, flax was associated with the workaday world; a flax-wench was “a woman of the lower class employed in making clothes from flax” (Sandra Clark).

Fabrics, especially those used in clothing, help us establish our identities, and are essential to Shakespeare’s works. High school and college level students can find Shakespeare linguistically and culturally inaccessible, yet teachers are usually required to teach his work at some stage.

In “The Fabric’s the Thing: Literal and Figurative References to Textiles in Selected Plays of William Shakespeare,” Nancy J. Owens and Alan C. Harris write that “by understanding the historical and social context of the terms used in the plays, the reader has a clearer understanding of the meaning of the plays as as well as a deeper appreciation of the importance of textiles used in dress throughout history. In addition, the analysis has validity for our own age as we use material in apparel to state aspects of, conditions of, issues in, or beliefs about our culture.” Understanding the context of fabrics mentioned in Shakespeare can lead us to a richer, more vibrant understanding of his work, and give us a way to engage with the time and context in which it was written. Owens and Harris also write that fabrics are “a ‘package’ of form and associated meaning that connects each individual to socially created, modified, and perpetuated cultural patterns.”

It’s important to note that many of the characters we can recognize as queer now would not have been defined as “queer” during Shakespeare’s time, but same-sex relationships were covered up, censored, and erased. By teaching his work from a queer perspective, we can combat harmful censorship practices and honor the beautiful relationships that existed. Miranda Fay Thomas writes that “looking for LGBTQ identities in plays such as Twelfth Night enable us to rediscover approaches to gender and sexuality that defy the binaries imposed on Western society since the introduction of the terms ‘homosexual’ and ‘heterosexual’ in the late 19th century. Finding queer love and identity in Shakespeare’s plays would not have been defined as queer back then, but the practice of censoring same-sex relationships in Shakespeare, from Benson and beyond, is still in the process of being righted and re-explored by both critics and performers. Twelfth Night, with its homosexual overtones and its depiction of a character presenting as an alternate gender, is a particularly rich case in point.” Fabric can help us talk about these issues further.

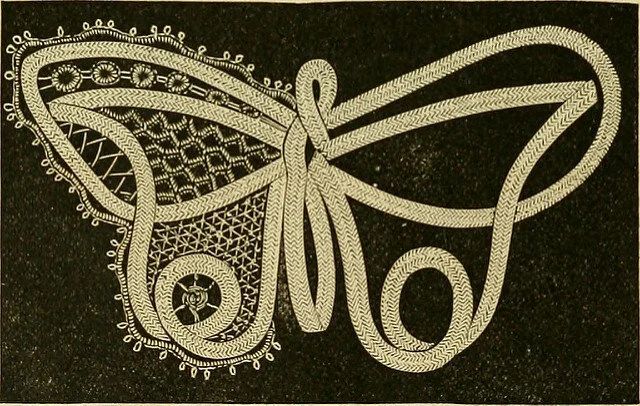

As an embroidery artist, my first encounter with the fabrics mentioned in Shakespeare was an exciting, multidimensional experience. It occurred to me that people who haven’t worked with fabric on a regular basis might not be able to engage with the text in the same way, and I wondered if I could create something that would help people experience this aspect of his work. For example, what exactly is changeable taffeta, the fabric that appears in Act IV of Twelfth Night? What’s the history of this fabric, and how is it used now? Knowing that this fabric is iridescent, sturdy, and noisy when one walks sheds light on the context in which it is mentioned. Contextualizing different fabrics can help us arrive at a deeper understanding of Shakespeare’s characters, how they speak to each other, and the world they inhabit.

Understanding the way people dress and what materials they value or devalue can help us understand their culture. The Shakespeare Globe Trust tells us that “in Shakespeare’s time, clothes reflected a person’s status in society—there were laws controlling what you could wear.” These laws were called the sumptuary laws, and although they eventually failed, the clothes one wore reflected a person’s status. The penalties for violating the law could range from the loss of property, the loss of a job, or the loss of one’s life. Materials and Fabrics Used in Elizabethan Era Clothing tells us that upperclass people “wore clothing made of velvets, furs, silks, lace, cottons, and taffeta. Knights returning from the Crusades returned with silks and cottons from the Middle East. Velvets were imported from Italy.” To contrast, lower class members typically wore wool, linen, and sheepskin, and were restricted to dull colors. Fabrics that typically belonged to the upper class were frequently worn by prostitutes in part to give men the fantasy of sleeping with an upper class woman.

To subvert sumptuary laws, some people began slashing their clothes, which exposed the color of the fabric linings (see: doublets). Actors were the only people in Elizabethan society allowed to wear clothes that were above their station. The realm of the play was the only arena in which people could wear whatever they wanted without punishment. The theater and the brothel were similar spaces in this sense, though one was legal and the other wasn’t.

The issue of women’s labor in the manufacture of garments is impossible to ignore. As Ellen Reiss writes in Clothing and Emotion, “The agony of millions of people has accompanied the manufacture of garments—has accompanied labor as such through the centuries. This agony includes children working at looms; young women jumping to their deaths during the Triangle fire because exit doors were locked; sweatshops; bodies sickened from horrible working conditions; lives spent in poverty. All this horror has arisen solely because that beautiful, kind oneness of selves and earth which is production has been forced to have as its basis the supplying of profit to some individuals.” Issues of gender and labor are incredibly intertwined in early modern times.

This Dictionary can be used to help students engage with the fabrics in Twelfth Night, Measure for Measure, and The Winter’s Tale, and to help teachers use material culture as a way to facilitate conversations about queer identity, gender roles and gender identity, sex work, women’s empowerment, class, and how fabric could literally cost you your life in Shakespeare’s time. The site includes teaching resources, including three companion assignments, along with additional resources for teaching Shakespeare from a queer perspective, and further reading.

I would like to thank Flickr Creative Commons for providing all of the photos for this project.

This project was born out of The Graduate Center, CUNY’s Interactive Technology and Pedagogy Certificate Program.

Bio: Madeleine Barnes is a writer, visual artist, and Doctoral Fellow at The Graduate Center, CUNY. She works mainly at the intersection of poetry, material culture, and queer theory. She is the author of YOU DO NOT HAVE TO BE GOOD (Trio House Press, forthcoming in 2020), Women’s Work (Tolsun Books, forthcoming in 2020), Light Experiments (Porkbelly Press, 2019) and The Mark My Body Draws in Light (2013). She teaches at Brooklyn College.